In my book Too Far to Walk I spoke of Nicolai Fechin, the great Russian/American artist who started a portrait of General Douglas McArthur that was never finished. The artist was a big part of my art gallery life and some of the paintings that I sold for $7,500 in 1978 are now worth $10,000,000 plus.

In my book Too Far to Walk I spoke of Nicolai Fechin, the great Russian/American artist who started a portrait of General Douglas McArthur that was never finished. The artist was a big part of my art gallery life and some of the paintings that I sold for $7,500 in 1978 are now worth $10,000,000 plus.

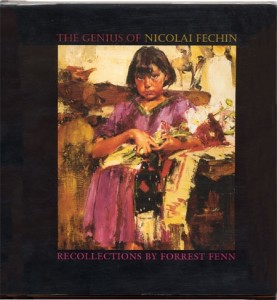

In my preface to The Genius of Nicolai Fechin, I wrote, in part:

Many of the words that follow are but the wayside notes and remembrances of an interested vagabond who climbed over the old walls of Taos and into the minds of those who played a starring role in the art history of that golden place. In the natural order of things, the years bring changes so insidious as to be almost unnoticed, none the least of which are in the minds of those who watched them happen. Long-gone thoughts may come seeping back in easy conversations among friends. It is from such discussions that I learned the most about Fechin.

So I wrote the story about a man who perhaps had more talent than the next fifty artists combined. But for me there was a sadness in his story. Toward the end of my book, under the heading Personal Reflection, I wrote:

Fechin died in his sleep on October 5, 1955, after painting a New Mexico landscape from photographs and sketches. His remains were cremated and held in abeyance in his daughter’s possession. Because his heart had always been in his mother Russia, his stated desire was finally to be interred there. So in 1974, I traveled with my wife and two daughters to Kazan, Russia, on the eastern reaches of a country I had visited many times before, this time to select Fechin’s final resting place.

For me Russia had always been a very foreboding country, even sinister. Yet Fechin had attended school there under the tutelage of Repin and received early accolades as his creative talents were first recognized and nourished. It was there also that he met his wife and experienced the first rewards of love and intimate companionship.

Arrangements for our visit had been made with a local commissar through Dr. Armand Hammer, an art business associate of Eya (Fechin’s daughter) and mine. Because Fechin had been an internationally celebrated artist who had brought glory to the state, there were only three places in the large cemetery where his burial would be approved, so his remains would rest near others of equal cultural importance. We planned to inspect all three sites and make a decision.

When our state car arrived at the cemetery, the day reflected my feelings. It was cloudy, and the dreariness of it emphasized by a steady rain that showed no signs of stopping. The memory of it is vivid to me even now, twenty-seven years later. As we walked down the paved path past hundreds of graves on both sides, our official escort, a big man, maintained a loud, guttural chatter in English; it did not stop.

After a few minutes, we approached an intersection in the walkways. To our right, only a few feet distant, a funeral was being conducted. In an open wooden box rested the body of an elderly man, as five or six mourners stood closely around. The men wore dark coats and hats, the women dark coats and babushkas. An officiator spoke softly, not looking up, his finger moving slowly back and forth across the pages of a large book. It was a powerfully solemn occasion, made more so by the steady patter of rain that fell into the open coffin. A few feet away, an elderly, bare-headed woman rummaged for food in a large, metal garbage basket, not looking up as we passed. Our guide seemed oblivious to the circumstances that, to me, seemed so profound, for he never paused in his bizarre rhetoric that was, by then, falling on numb ears.

We continued down the path and finally arrived at the first possible resting for Fechin’s ashes. As we huddled against the rain and mist, we were told that the markers surrounding this favored spot denoted the graves of those of high cultural accomplishments, equal to that of “Mr. Fechin.” I was embarrassed that the names he read were not known to me, but nodded approval as if I knew. My mood prompted me to insist quickly that there was no reason to continue the search, this would do. Besides, the weather was worsening. As we retreated back the way we had come, there was no sign of another human. I was thankful and commented to my wife, “If I thought I would be buried in this place, I am sure I would never die.”

Looking back at that experience now with the benefit of many years long since faded, the memories have not softened in my heart, and the dichotomy of Fechin’s earthly experience still weighs heavily on my mind. He had come from that harsh and foreboding place, through many of life’s greatest challenges. From his fragile beginnings it seems unlikely that he would have woven through such adversities to find that rare path to celebrity, admiration, and wealth in a foreign land, and then return, thirty-two years later to that somber spot.

The following year, Eya and her daughter Nikki (who her grandfather never met), also journeyed to Kazan as guests of the Soviet Union to lay her father’s ashes to rest.

Nicolai Fechin is still my idol, and I feel like I knew him, although we never met. Rarely has an artist’s work instantly, and so completely, seized the emotions of a passing observer, who, until that first moment, had been totally oblivious of his work.

Thanks so much for sharing that story, Forrest. There really is no place like home, or one that feels as such….:)

Your account has inspired me to learn more about Nicolai Fechin……so many different paths to enjoy while on The Thrill of the Chase…lol…and so many other treasures to be found along the way….

Thanks Mr. Fenn for introducing me to Nicolai Fechin. Since learning of him through your memoir, he has become a favorite. What an unusual master of form and color.

Thanks girls. It would be nice if everyone could leave a similar influence on the culture of this country.

In 2009 I had the pleasure of driving a Suzuki Alto car 10,000 plus miles from Goodwood, England to Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, over 4000 miles of which were in Russia. Art influences me so much that my luxury item I carried was a favorite book of short stories by Anton Chekhov. My one “must-do” while in Russia was to find a park with a nice, welcoming bench back-dropped by orthodox onion or helmet dome architecture in which I could read two of my favorite stories, The Lady with the Dog and The Bet while taking in the happenings around me, breathing in the air of a place I had once feared. Your writing took me right back to Kazan where I had stopped road-side to grab some tea, and a jar of honey that when I later tried it tasted like kerosene. Though there was a picturesque church in the distance, the dark clouds and mist of a gloomy mid-day in a strange land and the recent passing of a nuclear power plant so close to the road I got chills made me press on. Omsk finally provided what I had wanted in my must-do. And here, not too many years later, I have four great friends in my hometown that are from Kazan in which my one true memory is of the grey of the day. It is hard to imagine. I wish I had known of Nikolai Fechin. For providing me with my own reflection, Spasiba!

It’s great that Fechin did so much for culture in America. But maybe he would have liked some help from America to improve Kazan.

We all got off our couches and into the Rockies. Maybe the next step is to get us over to the emerging countries and make a difference there. Tourist dollars go a long way.

The gray skies are also sometimes blue; potholes can be filled; dirty buildings can be washed; gardens can be tended; and the poor can be comforted. Isn’t that what Fechin really wanted?

A picture paints a thousand words, and lives on long after they are gone. To tell a story through the strokes of a paintbrush, is quite a beautiful scene to see.

Pingback: Revolvingmirrors