Treasures from all around the world are out there for us to explore – thanks to Museums! In this Treasures of the Museum series, MW reaches out to museums all across the country to ask them Six Questions. It’s inspiring to learn – What Treasures are in the Museums? What are some interesting stories behind a few of these items at the Museum? What are some things to look for when we visit? AND are there any ‘lost treasures’ to be on the lookout for – for the Museums? Might you be the one to help find a lost treasure!

The following Six Answers are absolutely incredible. I appreciate Jennifer Sontchi taking time to share some highly interesting background stories on the Museum’s collection. There is a lot for us to experience, and incredible adventures to have, inside a Museum. Enjoy!

Six Questions with Jennifer Sontchi, Senior Director, Exhibits and Public Spaces, of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University

- 1Q) When did you start working with the Academy of Natural Sciences? Can you share some of its historical background?

I joined the Academy in 2008.

The Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia was founded in 1812 “for the encouragement and cultivation of the sciences, and the advancement of useful learning.” The oldest natural sciences institution in the Western Hemisphere, the Academy was founded when the United States hugged the Atlantic coastline and Philadelphia was the cultural, commercial, and scientific center of the new nation. Classic expeditions to explore the western wilderness, such as those led by Stephen Long and Ferdinand Hayden, were organized at the Academy. These explorers brought back new species of plants and animals, which were studied and cataloged, and they formed the foundation of the Academy’s scientific collections, which now contain more than 18 million specimens.

- 2Q) What do you enjoy most about working at the museum?

I love exploring the collections with scientists and digging around in our archives for content about our dioramas and how they were made. It feels like I am metaphorically running my fingers through a chest of gold coins, gems, and tiaras. The museum collections value to science is literally priceless—and I feel very lucky to share them with the world.

- 3Q) Do you feel there is one exhibit or artifact that the museum is most known for? Can you share some interesting facts about it?

When I talk to visitors who grew up in the Philadelphia area, they nearly always recall our moose diorama (moose are much bigger than people imagine and this diorama makes a major impression on youngsters).

Our moose has a wonderful history:

Back in the early 1930s, New York’s American Museum of Natural History and Chicago’s Field Museum had impressive moose mounts on display. The Academy wanted an equally outstanding specimen to show our interested visitors. In 1933, Academy benefactor Nicholas Biddle traveled to Alaska in search of such a moose. The one he collected was very good, but its antlers were a tad smaller than the moose antlers at the other two museums.

The taxidermist commissioned to mount the moose, Louis Paul Jonas, and the Academy’s Director of Exhibits, Harold Green, found a larger pair and secured them to the head of the moose. When the diorama opened in 1935, we could confidently say that the Academy had the largest moose mount on display in North America. We call it our “Franken-Moose”.

- 4Q) Is there some often forgotten item that shouldn’t be missed when visiting?

Yes!

In 1858, hardly anyone had heard the term “dinosaur.” But Academy member William Parker Foulke had learned about these creatures while attending Academy meetings. That summer Foulke had dinner with a Haddonfield, New Jersey, farmer who reported some bone-like objects that workers had uncovered 20 years earlier. After confirming that these objects were fossilized dinosaur bones, Foulke persuaded Joseph Leidy to come to Haddonfield. The bones Foulke dug up led to the assemblage of the most complete dinosaur skeleton of the day. Leidy named the species Hadrosaurus foulkii (“Foulke’s bulky lizard”).

Ten years later, an Englishman artist named Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins offered to mount the skeleton and in 1868, we unveiled the world’s first mounted dinosaur skeleton. The exhibit was an instant sensation, drawing people from all over the world.

Credit: Mike Servedio/ANS

- 5Q) What do you feel is the most valuable ‘treasure’ of the museum? It might not be a monetary value, but of a historical value or even sentimental?

The enormous meteorite (an iron space rock) on display in North American Hall is my favorite treasure. It is one of several pieces from the Canyon Diablo meteorite that plowed into the Arizona desert 50,000 years ago. The meteorite created the most famous and best-preserved meteorite crater in the world, the Barringer Crater. Meteorites in general are very valuable to collectors and can be worth their weight in gold at some auctions. Ours weighs 480 pounds!

- 6Q) Is there any advice you would have for those wanting to visit? Are there best times of the day, or days of the week to come? How long should visitors allow on their schedules to explore the fascinating exhibits?

Due to Coronavirus safety measures for our staff and visitors, we are open Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays. Online tickets are recommended and available at www.ansp.org.

You can visit the museum in about 90 minutes. Please check our website for updates!

- Bonus Q: ‘Is there an item, a ‘lost treasure’ so to speak, that the Museum is on the lookout for? Might it be out there to find?’

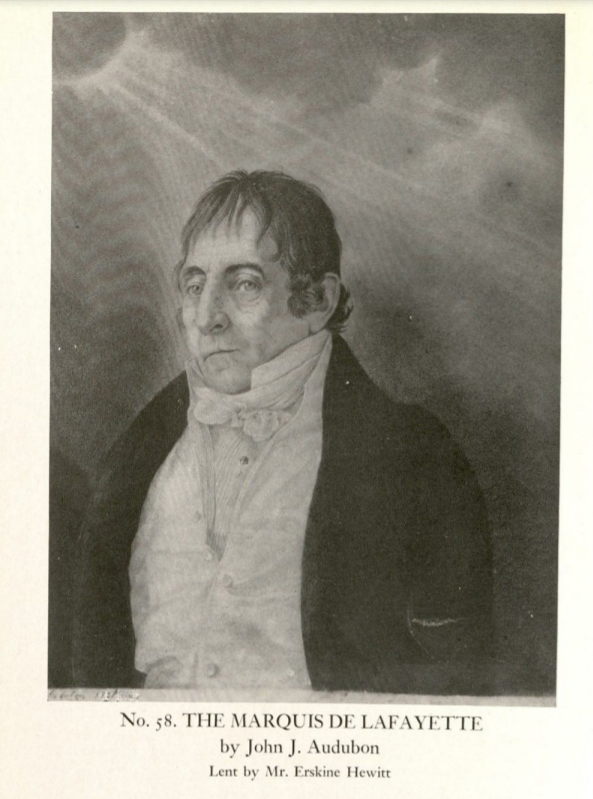

Yes! A “lost” portrait by John James Audubon

In the spring of 1938, on the 100th anniversary of the publication of John James Audubon’s classic Double-elephant-folio The Birds of America, the Academy of Natural Sciences held the first national exhibition on the life and art of the well-known artist-naturalist for whom the National Audubon Society was named. We borrowed original paintings and artifacts from public and private collections across the country – 140 things in all. These were well documented in an exhibition catalog, so we know exactly what was shown. In the 82 years since then, a number of the things that were exhibited have been “lost,” which is to say their current location is unknown. One that we would especially like to find is a portrait of a distinguished, elderly gentleman that was painted by Audubon in about 1820.

At the time it was exhibited, the portrait’s owner thought it was of the Marquis de Lafayette. This is almost certainly not the case, as Audubon never met Lafayette, and the portrait does not resemble him. Still, it is a very good painting and we would love to be able to borrow it back and put it on exhibit to reveal this little-known side of Audubon’s artistic career, which is discussed in detail by the Academy’s Senior Fellow and Curator of Art and Artifacts Robert Peck in the current (Autumn) issue of Antiques and Fine Art magazine. If anyone recognizes this portrait, once owned and loaned to the Academy by Erskine Hewitt of New York, please let us know.

Come Explore the Academy of Natural Sciences