Samuel Prichard’s ‘Masonry Dissected’

A Masonic Exposure that Changed Freemasonry

Article by Duncan Burden

A Masonic Exposure, or Exposé, is a publication released to the general public claiming to, at times successfully, revealing the secrets of Freemasonry. Samuel Prichard’s ‘Masonry Dissected’, released on the 20th October 1730 in London, was exactly that. To appreciate the significance of the impact this little pamphlet had on Freemasonry, it is important to take a moment to appreciate both the embryonic growth of Speculative Freemasonry at the time and social culture of early 18th century England.

Although Masonic Lodges had been in existence for almost half a century before, it was in the early 1700’s that a real sense of universal purpose was beginning to be established. No greater evidence of this can be found than in the forming of the first Grand Lodge exclusively for Speculative Freemasonry, namely Premier Grand Lodge of England on 24th June 1717. Originally this Grand Lodge titled itself only as the ‘Grand Lodge of London and Westminster’, yet it is generally assumed that it adopted the more regale title of ‘Premier Grand Lodge of England’, to elevate and distinguish itself from the older Operative Grand Lodge of York.

The Grand Lodge of York had existed from when Stonemasons had gathered in organized guilds to teach and work with stone, but, although it appeared to acknowledge the development of the new purely ‘Speculative’ style of Masons and their Lodges, they didn’t show any significance to its development.

This was the purpose of the Premier Grand Lodge of England, to establish and support a purely Speculative version of this new, and popular style of Masonry. The focus of Speculative Freemasonry was purely philanthropic, to create an organization that took men of good character and would inspire them (through a bonding and educational rituals) to be better.

The incentive to be a Freemason was two-fold. The first was to be an individual another person saw as, true or not, a good moral person. During the 17th to 19th century, to be seen as a moral individual was the height of fashion, in fact the incentive to be seen as moral was more important than the actual emotional benefits of being a good person. As such, being a Mason was seen as a badge of approval and helped a person’s recognition in society.

The second incentive was the ‘rights and privileges’. Because Speculative Freemasonry instilled so much importance to Brotherly love and support, to be Mason assured the members they had support if times were hard, including financial. In this sense, to be a Mason was sort of like taking out an all-inclusive insurance policy. In the 18th century there was no free medical help, no general insurance on healthcare, no income support, so be a Freemason gave a member this security. Additionally, with Freemasonry being nationwide, a travelling Mason could be assured of this help wherever they may be. For example, if you had become a Freemason in London, and moved to Nottingham, all you had to do was go to a local Lodge in Nottingham, prove you were a mason by giving the secret password and handshakes, and help would be given.

All this fueled the growth of Freemasonry, and the desire to be one – but Freemasonry wasn’t free and not everyone was invited to join.

Public interest in this new version of Freemasonry grew. With that interest came the opportunity to make money. From 1723, little booklets began to be published ‘claiming’ to reveal the secret handshakes and passwords of Freemasonry. These were sold on the pretense that if you bought the pamphlet you could walk in a Lodge, be recognized as a Mason, claim to need help as a Freemason, and it would be given, all for the cheap price of the booklet – and so the Masonic Exposé market was born.

One of the most popular and influential was Samuel Prichard’s ‘Masonry Dissected’ that caused the first real controversial impact on Freemasonry itself.

The pamphlet was incredibly small, its first edition was only 33 pages and measured on 7 inches by just under 5. It was offered on sale through the newspaper the ‘Daily Journal’. Several reprints came in swift succession. Although the title ‘Dissected’ seems to imply that the booklet offers a detailed account of the mysteries of Freemasonry, that is not really what the term meant back in the 18th century. Back then, scientists were cutting up animals and humans in public shows, dissecting them to show the workings inside. This was all Prichard’s book was claiming to do. It should be appreciated that during this time virtually nothing was known about what happened in a Masonic Lodge. There was no internet, not easy access to libraries or bookshops with swathes of titles about Freemasonry. As such, all snippets of information was considered new and complete.

The booklet itself opens with two comments from Prichard himself. The first is an oath that everything as written is genuine, and the second is actually a Dedication to fellow Masons and to the Fraternity itself. It is impossible to prove if Prichard felt he was honorably justified in printing the publication, feeling that, somehow, he was helping to promote Freemasonry, or providing a service, but it is more likely that the statement was added as a slight attempt in ‘marketing’, making his work sound more officially approved and genuine.

Even so the text, even to a modern Mason, is clearly genuine, or at least became so popular that Freemasonry became to be defined to what Prichard wrote.

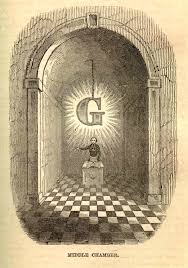

Within the first few lines of the opening commentary, he lists that Freemasonry is based on the Liberal Arts and Sciences, with specific relevance to the subject of Geometry. The Seven Liberal Arts and Sciences are still the primary subjects a Mason is instructed to study today, and several versions of Masonic ritual still highlight that Geometry is the most important. He goes on to give a brief mythological history of Freemasonry, which would have been recognized by any Mason of his time, as its stems from the history as composed by the famous Dr Anderson’s Constitutions of Freemasonry of 1723.

Following this opening Prichard goes on to offer a line by line script of how each of the three ceremonies of Craft Freemasonry are performed. This includes how to stand, what was expected to be worn, times of day – everything a non-Mason would require to be recognized as a Brother.

The impact of this, and other similar texts, was immense. The Premier Grand Lodge of England had only been operational for 13 years, with many of its founders still paving the way for its success. In the minute book of the Grand Lodge, on the 15th December 1730, it is recorded that Prichard’s text was not actually genuine, but that a message should go out to all Lodges that they should be careful of impostors, and that no stranger should be admitted unless they are known to at least one existing Brother.

Even so, ‘Masonry Dissected’ and a previous booklet called, ‘The Mystery of Free-Masonry’, published earlier in the same year, are both referred to in the minute book of the Grand Lodge of England and relate to sanctions of change or defense against the consequences of the public knowing their contents. It is believed one of the preventive measures was to change the order of the passwords for the degrees.

These changes in ceremony didn’t go well, and by 1751 some Brethren and Lodges added them to other grievances they already held against the Premier Grand Lodge of England, and formed their own alternative Grand Lodge, the Grand Lodge of England according to the Old Institutions. Believing themselves to be maintaining original versions of Freemasonry, they become known as the ‘Ancients’ and the members of the Premier Grand Lodge became referred to as the ‘Moderns’. This rift lasted until their union in 1813, creating the present United Grand Lodge of England.

Through this unification, a unique event happened, for the sake of harmony between the existing Brethren, a uniting of the rituals and the structure of the degrees had to be re-established. Whereas the rituals and structure of Freemasonry of around the world continued to naturally grow and establish themselves by natural selection, in England it stopped and was scrutinized, analyzed, defined and distributed. Although varieties of rituals still exist in England, the union of 1813 established finally that Freemasonry consists of three degrees and three degrees only; namely the Entered Apprentice, Fellowcraft and Master Mason, the latter completed by the Holy Royal Arch. It also insured, possibly by default, that the following sentence was in all approved versions of the ceremonies, that Freemasonry is a ‘system of morality, veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols’.

Linguistically English Freemasonry is the most structurally defined system in the world, but it is unlike to have been the case if it was not for the publications such as Samuel Prichard’s ‘Masonry Dissected’. The work is now in the public domain, and is still relevant now, as it was just under 300 hundred years ago.

~Article written by Duncan Burden

Duncan Burden enjoys researching history. Although he often writes on Masonic issues, since he has been a Freemason for most of his adult life and is a member of various Masonic bodies, such as the Royal and Select Master Masons, and Operative Masons, he takes pleasure in writing on all historic, mysterious, and exciting topics.

He was born on the Norfolk Coast, and now lives in Hertfordshire, England.