![Sator_Anagram[1]](https://mysteriouswritings.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Sator_Anagram1-300x294.jpg) Once called an Alchemy of Wit, an anagram is defined as the forming of a new phrase or word by transposing the same letters from another phrase or word. All letters must be used and none are to be added in order to be considered a true anagram.

Once called an Alchemy of Wit, an anagram is defined as the forming of a new phrase or word by transposing the same letters from another phrase or word. All letters must be used and none are to be added in order to be considered a true anagram.

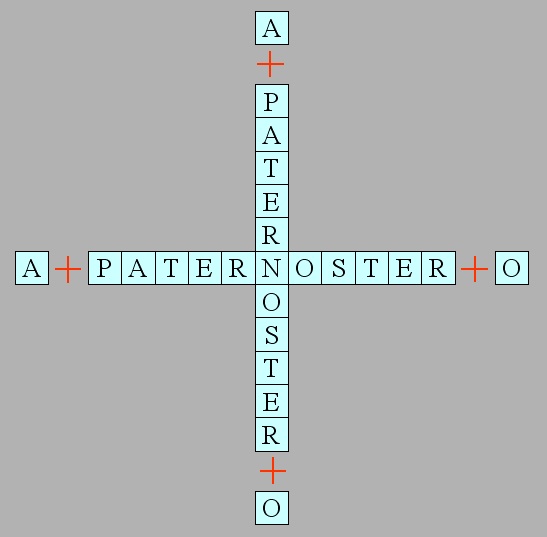

One of the most famous anagrams is that found of the Sator Square in 79AD in the city of Pompeii. More on the Sator Square here.

Today, anagrams are commonly thought as fun and entertaining word games. They appear as scrambled word exercises which are played to pass the time or are often used as clues in armchair treasure hunts or games. The anagrams can be as simple as writing the original word in reverse, like CAT to TAC or switching positions, like ARC to CAR. Complicated and complex anagrams can be created as well. Whole paragraphs can be changed to provide an entirely different meaning or add depth to the initial one.

A professional anagrammatist strives to form a connection with the newly ordered letters from the initial letters. For instance, as shown in the Harry Potter series with ‘Tom Marvolo Riddle’ being changed into ‘I Am Lord Voldemort’; the transposing revealed who he really was. This clever relationship of names was one of the first uses for anagrams.

Cabalists were widely known to have applied anagrams to people’s names. Called Themuru, implying change, the rearranging of letters in a name was believed to unveil hidden meanings and the spiritual natures correlating to that person. Pythagoras (6th century BC) is also thought to have used anagrams to discover a person’s destiny.

An example of one’s destiny being revealed through an anagram is found within a story of Alexander the Great in 332BC. One night, soon before his siege of Tyre, Alexander was said to have had a disturbing dream about a Satyr attacking him. After asking his sages about it, the meaning of the dream was realized by anagramming the Greek word for Satyr. The sages foretold the victory of Alexander the Great by declaring the anagram,‘Tyre is thine’, announced his destiny.

Anagrams became extremely popular in the middle ages. Regularly known users during the period were scientists. Unwilling to reveal what they knew, either out of fear for offending the church or unready to present all facts, they concealed their findings by applying anagrams. Releasing a collection of letters, which were know to hold meaning but not understood by others, scientists were still able to lay claim to their discoveries. Galileo is known to have created the following string of letters which he then sent in a letter to a friend:

Smaismrmilmepoetaleumibunenugttauiras

He later disclosed the muddled string as the anagram for Altissimum planetam tergeminum observavi (I have observed the most distant of planets to have triple form).

Another common usage of transposing letters of the time has been recognized in Biblical anagrams. One of the most popular Latin anagrams known is formed from a question asked by Pilate to Jesus in John 18:38:

“Quid est veritas?” translated as “What is Truth?”

No answer was provided to Pilate. However, an anagram unveiled, ‘Est vir qui adest’, which translates to, “He is the man before you”. Those with eyes to see knew the answer and the deeper level of awareness remained hidden to others.

Isaiah is believed to have predicted this event in Verse 53:7; “He is brought as a lamb to slaughter, and as sheep before her shearers is silent, so he did not open his mouth.”

Secretly, powerfully and entertainingly used in the past, anagrams made their way to games and common forms of amusement. The American company, Selchow & Righter Co. published the game of Anagrams in the 1870’s. Soon following in the 1890’s were the game companies of Milton Bradley and Clark & Sowden. Mcloughlin Bros. and Parker Brothers produced their own version of Anagrams as well. Presently, a well-liked game of Bananagrams is often played.

Like many things so cherished in the past, anagrams still hold their fascination. Whether seriously or amusingly applied, they will continue to offer a mysterious attraction.

End note: For those who worked on the Maranatha puzzle, one will surely see the connection (intended or not) to Pilate’s question and the July 2006 Clue of “As with most Truths the answer is right in front of you, and you have been told where to look”

Sources:

Wheatly, H. B., Of Anagrams, reviewed April 2012

Percy, Reuben, Relics of Literature, reviewed April 2012

Pingback: What do Anagrams, Tea Leaves and Pebbles Have in Common? | Women of Grace

Why would cabalists make anagrams of people’s names? One possibility (and this is just speculation) is that if you know somebody’s name and an anagram of it (maybe their “true name”) you could use that information to encode with a transposition cipher. For example, let’s take “quid est veritas?” and “est vir qui adest”. Let’s say the order of letters in “quid est veritas?” is 1-2-3-4 5-6-7 8-9-10-11-12-13-14. Then, the order of letters in “est vir qui adest” is 5-6-7 8-3-10 1-2-11 13-4-9-14-12. You could use the exact same pattern to jumble letters to encode something else.

Another thing: Galileo’s anagram had 37 letters. It’s impossible to unscramble an anagram of that length without having some agreed method to do this (that presumably Galileo shared with his friend). The problem is that such a long anagram could become hundreds or even thousands of valid sentences, and it’s impossible to tell which one is meant without more information.

I thought that, since Tom Marvolo Riddle was an anagram, what if Voldemort was an anagram as well? Clearly, those letters don’t work too well for an anagram in English. Then I came up with this: “LDV e morto”, Italian for “LDV is dead”. LDV is Leonardo da Vinci, of course, and it makes sense that a sentence about Leonardo would be in Italian. Alternatively, it could be “DLV E morto”, meaning “555 He’s dead”. 555 being a number with plenty of Masonic connotations, that’s why the obelisk in Washington is 555 feet tall, like Dan Brown says in “The Lost Symbol”. OK, maybe JK Rowling didn’t mean it to be an anagram, but until she explains the name, I’m sticking to my conspiracy theory.