In 1960, a Belgian explorer, Jean de Heinzelin de Braucourt (1920-1998), discovered one of the earliest and most curious mathematical artifacts known to us today. Named the Ishango Bone, after the region from which it was found and material used for its fashion, this historical object provides an intriguing glimpse into the thoughts of an early community and person who created it.

In 1960, a Belgian explorer, Jean de Heinzelin de Braucourt (1920-1998), discovered one of the earliest and most curious mathematical artifacts known to us today. Named the Ishango Bone, after the region from which it was found and material used for its fashion, this historical object provides an intriguing glimpse into the thoughts of an early community and person who created it.

The bone was unearthed while excavating the northern banks of Lake Edward in Africa. Lake Edward is a headwater of the Nile and rests below the continuously snowcapped high peaks of the Rwenzori Mountains; or as Ptolemy called them, the Mountains of the Moon. It was here, in this lush and beautiful setting, that ruins of a lost people buried beneath debris of a past destructive volcanic eruption, were rediscovered. The Ishango Bone, along with the site’s other artifacts, are believed to date back to appx. 20,000 BC.

The Ishango artifact is a small fibula bone of a baboon and is noticed to have three different columns of marks carved into its surface. Attached to one end of this remarkable object is a sharp piece of quartz, possibly the tool used to create the bone’s scored lines. It is these lines that fascinate. They present an observer with a mystery to ponder; what was the maker thinking? What was he making note of with these lines, and why?

These questions are for anyone to try and answer.

Although earlier bones with carved in lines have been found, like the Lebombo Bone dating to over 35,000 years ago, the Ishango Bone is believed to be something more extraordinary. The previous found relics are classified as tally sticks. These discovered sticks of bone with notches were believed used to aid in memory or recording. They may have been used in attempts to quantify time. Although significant, the Ishango Bone seems to go steps beyond mere counting marks.

The Ishango Bone’s marks demonstrate an astonishing knowledge of mathematical ideas for the age in which it dates. The groupings of hashed lines illustrate number patterns that render an appreciation for figure. Although it is a possibility the lines coincidentally show this numeric significance, and were used as another function, say to make the bone less slippery while handling, it is hard to fathom this. There are three separate columns of various groupings and all hold recognized meanings connecting to each other. You can decide for yourself, however.

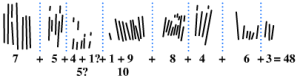

The column’s marks are grouped in the following ways.

Shown in the first column is an understanding of doubling or dividing by 2; 3 lines next to 6, 4 lines next to 8, and then 5 lines next to 10. It would appear at first the 5 and 7 grouped lines at the end are out of place, but these are prime numbers before the number 10, and may indicate a deeper grasp for the inability of certain numbers to divide simply. If intentional, it would be the first recorded insight into primes known. The next record of knowledge on primes doesn’t come until much later; on the Rhind Papyrus dating to about 1650 BC.

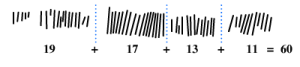

The second set shows additional primes between the number 10 and 20. Here displayed are line sets of 19, 17, 13 and 11. It suggests the thought on failure of amounts to divide equally continued beyond just 5 and 7.

The third group offers a look at odd numbers 9, 11, 19, and 21. These are ‘one less than’ and ‘one more than’ the numbers 10 and 20. 10 and 20 are natural human numbers to contemplate for they are the number of fingers, and toes we all have. The addition of 1, with 4 and 9, to give 5 and 10, seems mused upon by the bone’s creator, and is indicated, within the first column, as well.

Furthermore, as illustrated, the numbers of the columns add to 60, 48, and 60. Multiples of 12. Was this deliberate? 12 is often found noteworthy in beginning number systems because not only does it coincide with the amount of phalanxes of the fingers (not including thumb) and used for easy calculations of fractions, but connects to the lunar cycle with months of the year. Perhaps the first column’s 5 and 7 grouped lines somehow connected to 12’s importance (5+7=12).

Today, numbers are taken for granted. The Ishango Bone brings back the opportunity to think like someone who is first learning the value of number and take number into consideration. Casting thoughts of today away, and imagining sitting on the side of Lake Edward with the warmth of the sun, what would you wonder about ‘number’?

The bone’s complete message may not be fully discovered and you may be the one to realize more of the bone’s creator initial thoughts.

Could it be a spendal for string or yarn and the lines are cut during rotation?

It may be that it was a way of keeping track of different things

That is why the lines are short and long. Just a thought.