What Happened to Bloody Island?

Article Written by John Davis

On a brisk morning, with wind wafting off the Mississippi river across from St. Louis, Missouri, the men faced each other with pistols, at barely more than arm’s length. They’d come to shoot at one another because of an ‘offense against honor’.

The place, or ‘field of honor’, was Bloody Island.

It was reached by rowing across the untamed river from 1831 St. Louis, already a major port. Because Thomas Biddle, the challenged, was nearsighted, he had only one hope of survival. Indeed he’d responded to Congressman Spencer Darwin Pettis’ challenge to a duel by accepting. Pettis had reason to believe it was Biddle who beat him in an alley with a horse whip some time earlier. Yet Biddle knew he himself, as the recipient of the letter of invitation to combat under the Code Duello, had the choice of weapon and circumstances.

He chose pistols at only five feet of separation. He’d hoped, as was often the case, that sense would intervene. Under these suicidal conditions, surely someone would call honor salvaged without a shot fired. Using purpose made English dueling pistols, on the order of the judge, they turned at one pace, aimed, and…..fired.

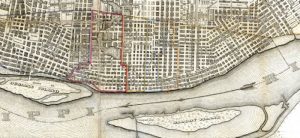

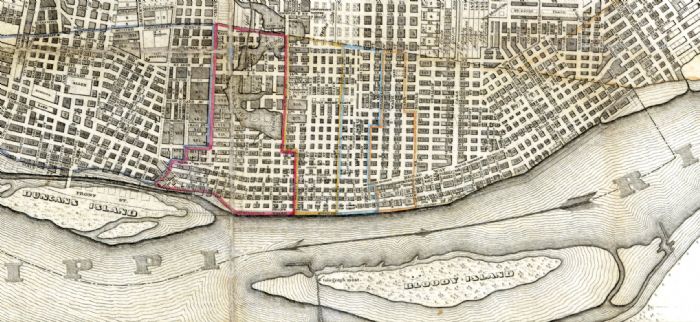

Bloody island was a large, tree and brush filled sandbar which sat near the Illinois side of the Mississippi river. Lying between the jurisdictions of two great states, it had become the focus of vice. Illegal cockfights, lawless bare fisted boxing and gambling, and the outlawed duel between offended parties all took place there. It was, in a literal way, no man’s land. Where there was no law, there was always someone to take advantage, so long as the law looked the other way.

Dueling, or individual combat under a rigorous social code which employed seconds, doctors, judges and support staff, was outlawed in Missouri in 1822. A vibrant, rough and ready frontier justice had to be overcome, and the rule of law introduced, even to the self styled aristocrats of early 19th century America. For that reason, the upper crust of frontier America, the judges, lawyers, editors, and politicians whose ‘honor’ was easily offended, used the island as a haven to practice their crime. For it was officially a crime to duel, to deliberately attempt to harm and possibly murder someone to satisfy a perceived slight.

And perceived slights abounded. One man shot another because he’d been called out for ‘notorious poltroonery’, while another went on to a potential murder because he’d been publicly called a “dish of skimmed milk.” Accusations in newspapers, cries of property and tax fraud, implications of sexual misconduct, cries of defiance of racial law, and imaginative slurs abounded. Yet, America in those days, particularly in the new regions beyond the Alleghenies, too often settled their scores by violence when verbal contests got too hot. Bloody Island was, in a word, lawless.

A politician, Thomas Benton, was called a tax cheat by Charles Lucas. Benton replied saying he’d ignore such accusations made by “any puppy who may happen to run across my path.” Puppy was a word one gentleman never called another. In the end, Lucas lay dead in his own blood on Bloody Island.

Thomas C. Reynolds, a future lieutenant governor of Missouri, called out Benjamin Gratz Brown. They’d argued about emancipation, with twinges of race baiting in the mix. Reynolds escaped being hit, while Brown’s leg was shot so badly he limped, even throughout his later Missouri governorship!

Abraham Lincoln, called out by an Illinois State auditor for anonymous accusative letter writing, (said by some to have come from Lincoln’s wife), chose broadswords on Bloody Island. Sense intervened, or perhaps Lincoln’s demonstrably long reach and able skill with the sword did so. Thus, ‘honor was served’ and both men left without a fight. Others however, continued to fight it out.

Bloody Island as a place of mayhem finally came to an end due to economics. The Mississippi River’s vagaries pushed the main channel closer and closer to Illinois. St. Louisans led Missouri politicians to call on the Federal Government to prevent its riverport from become an inland city. Lieutenant Robert E. Lee, US Army Corps of Engineers, arrived. He it was who established the dams and re-channeling which directed the river’s silt toward Illinois. Finally, after years of waterborne deposits of earth, Bloody Island was finally built into the Illinois mainland. Bloody Island disappeared.

Oh, and at five feet, Biddle and Pettis killed each other.

~Article written by John Davis

Read More from John

John William Davis is a retired US Army counterintelligence officer and linguist. As a linguist, Mr. Davis learned five languages, the better to serve in his counterintelligence jobs during some 14 years overseas. He served in West Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands during the Cold War. There he was active in investigations directed against the Communist espionage services of the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact. His mission was also to investigate terrorists such as the Red Army Faction in Germany, the Red Brigades in Italy, and the Combatant Communist Cells (in Belgium) among a host of others.

John William Davis is a retired US Army counterintelligence officer and linguist. As a linguist, Mr. Davis learned five languages, the better to serve in his counterintelligence jobs during some 14 years overseas. He served in West Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands during the Cold War. There he was active in investigations directed against the Communist espionage services of the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact. His mission was also to investigate terrorists such as the Red Army Faction in Germany, the Red Brigades in Italy, and the Combatant Communist Cells (in Belgium) among a host of others.

His work during the Cold War and the bitter aftermath led him to write Rainy Street Stories, ‘Reflections on Secret Wars, Terrorism, and Espionage’ . He wanted to talk about not only the events themselves, but also the moral and human aspects of the secret world as well.

And now recently published in 2018, John continued his writing with Around the Corner: Reflections on American Wars, Violence, Terrorism, and Hope.

Two powerful books worth reading.

Read more about them in the following Six Questions:

Six Questions with John Davis: Author of Rainy Street Stories

Six Questions with John Davis: Author of Around the Corner

Water balloons at 5 paces is the best choice.

You both get wet and everybody ends up laughing.

Thank you for these comments. I’m still astounded by how grown men would quite literally kill each other over slights. In fact, as bloody island shows, governments looked the other way, even though dueling was outlawed. With a middle ground like the Mississippi River’s Bloody Island, they could pretend ‘it wasn’t their problem’.