(The following article was first published in The Heretic Magazine Vol. 7 (Oct. 2015 issue)

Board games are intuitive creations found at the very first orderings of civilizations. They offer powerful insight into key beliefs and habits of the societies who played them. But unfortunately, games are often neglected by researchers’ considerations in academic studies. They are passed over as mere child’s play, and are mistakenly assumed to hold only frivolous information.

This huge misapprehension of a game’s historical contribution is becoming recognized and corrected. It’s being realized older board games of the past were created not only for enjoyment, like many today, but for also enriching and developing a man’s understanding through the game’s play.

From a game’s objective, method of play, design, pieces, and board, players were able to experience and learn important concepts. Wonderfully, we can learn these past ideals by identifying a game’s purpose and hidden appeals. By doing this, the forgotten prizes of games can be appreciated and are helping to place missing pieces into history’s vast puzzle.

Rithmomachia: The Battle of Numbers

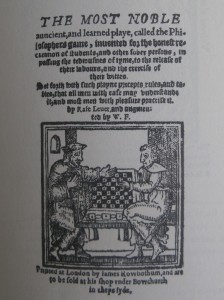

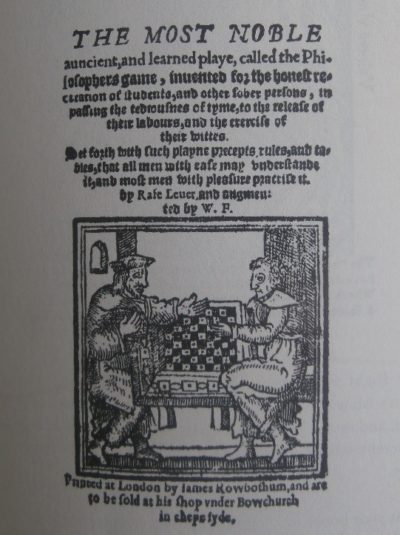

One such board game that provides an amazing perspective into the time it was played is a game called Rithmomachia, also known as The Philosopher’s Game. Researching the history and the surrounding details of the game takes a person on a fascinating journey. Few people today have heard of Rithmomachia, but it was played passionately by some of the most influential men in Europe. It was enjoyed for centuries between the years 1000 CE – 1700 CE and was continuously respected during this age of great change and development.

Rithmomachia’s high regard and survival through these turbulent times suggests it held a meaningful, extraordinary, and deep-rooted purpose. A purpose not wished to be lost, and one that may have found its way into the foundations of Freemasonry.

The game’s name derives from Greek Rithmos (number and rhythm) and mache (battle) for ‘battle of numbers’: Rithmomachia. And although this gives a military connotation, the game was mainly concerned with formulating mathematical harmonies based on the philosophy of Boethius. From a strategic battle between two players, who contemplated number and their proportional relationships in order to capture opponent’s pieces, a greater goal of awareness for Number was achieved by players. Experiencing the essence of numbers helped players realize Divine Truths not easily taught by words. The game was often referred to as Wisdom itself.

Description of the game in a 1030 CE instruction manual dates it back to at least this time. It was written by a German Monk named Asilo and he is often considered the game’s inventor. Asilo used the game to strengthen player’s commands on the esteemed works of Boethius. Boethian ideas were being taught within the monastery at Wurzburg, and from this assumedly first introduction of the game, it quickly spread happily throughout Europe.

Boethian Philosophy

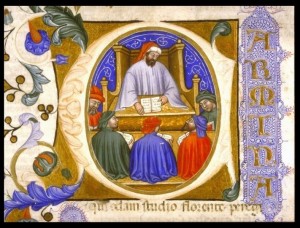

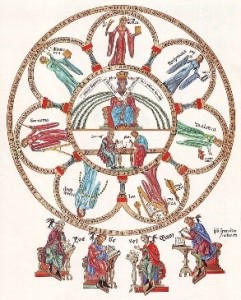

Rithmomachia embraced Boethian Philosophy and was a tool to fully nurture Boethian ideals into the minds of players. Boethius (475-526 CE approx.) was a philosopher who authored an extremely influential work of the Middle Ages and Renaissance; entitled Consolation of Philosophy. His previous writings on number theory, which were used to form Quadrivium studies of Arithmetic, Geometry, Music, and Astronomy, all found conclusion in his Consolation of Philosophy. As stated by Michael Masi in his translation of the De Institutione Arithmetica, “The Quadrivium is a four-fold path to the study of the moral Truths of the Consolation, and Boethius is insistent that these steps be taken carefully and methodically.”

Boethius’ works are consistently referred to in writings regarding The Philosophers’ Game. The two are inseparable. Rithmomachia appeared when Boethian texts began to be used in teachings of the Seven Liberal Arts and Sciences and was played so men could better experience principles of the Quadrivium.

Boethius was influenced greatly by Pythagorean thought and much of his work incorporates the belief that ‘all things known have number’. He was inspired by Pythagoras’ discovery that pleasing sounds of music held a hidden pattern of number. Boethius’ further awareness that harmony could be realized in all things, not just musical notes, and that they conceal recognizable and intelligible numerical relationships, captured his main focus. He expanded his notions of proportions to all levels of the Quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy) and offered an all-encompassing view of the harmonious beauty of creation.

The Philosopher’s Game was based on these momentous discoveries and helps us grasp the extreme importance the teachings of Boethius and the Seven Liberal Arts and Sciences had in this time. Manuscripts, poems, books, etc. giving high regard to the game provide us with knowledge to recognize the magnitude felt for Boethian/Pythagorean values by those who played it. Surely since the game was held in such grand honor, the principles it revealed were admired even more so elsewhere.

A Master’s Seal

The game spread zealously through the early monasteries, cathedral schools, and later into the universities of Europe. It was even one of only two games allowed to be played in Utopia; Thomas More’s venerated literary work expressing the perfect society. Other games were thought not to be worthy enough of play here, but Rithmomachia was prized, since it was believed to enhance the Soul.

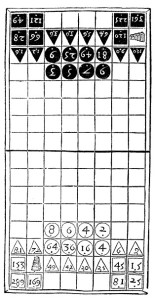

The game utilized a checkered board of squares 8×16 (a double joined chess board). The pieces were of the three primary geometrical shapes; circle, triangle, and square. Each piece carried a number and the player’s pieces were either White or Black. White numbered pieces developed from a base of evens (2-4-6-8) and black pieces from a base of odd numbers (3-5-7-9). From these, applying Boethian concepts, all pieces displayed number, and a battle of numbers based on proportions, means, and harmonies could commence.

Movement of pieces were determined by their shape. Circles moved one space, Triangles moved two, and Squares moved three.

This is basically where agreement on rules stopped. Numerous variations on how to capture and win are found within manuscripts sharing the game. These differences did not affect the ultimate purpose of the game, however. No matter how a person played the game in detail, Boethian thought was applied, practiced, and learned. The concept of number for revealing Divine Nature was given. Through the game’s working play, man acquired insight into mathematical Truths.

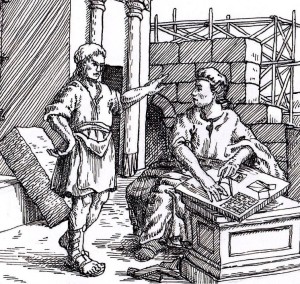

This opinion of players discovering the Divine through play may seem odd today. But this notion of how play enriches a man’s mind, body, and soul can be better understood by comparing it to how an instructor teaches a student of dance.

Some things are taught best by example and must be learned through experience and practice. For activities, like dance, simply listening or watching, does not provide the complete manner to develop desired skills. A student must apply actions, and practice what he is shown, for the master to be established in himself.

This system of emulating a Master was deemed to be a powerful method of conveyance. An example of such is found in the attitude of Hugh of St. Victor. Hugh of St. Victor (1096-1141CE) was a prominent theologian at the Abbey of St. Victor in Paris, and in the book, The Envy of Angels, C. Stephen Jaeger includes the following revealing passage written by Hugh of St. Victor:

“Why do you suppose, brothers, we are commanded to imitate the life and habits of good men, unless it be that we are reformed through imitating them to the image of a new life? For in them the form of the image of God is engraved, and when through the process of imitation we are pressed against that carved surface, we too are molded in the likeness of that same image…We long to be perfectly carved and sculpted in the image of good men, and when excellent and subline qualities….stand out in them, which arouse astonishment and admiration in men’s minds, then they shine forth in them, like the beauty in exquisite statues, and we strive to recreate these qualities in ourselves.”

Hugh of St. Victor felt man could be read like a book. A Master’s actions, posture, dress, speech, temperament, his totality, revealed the Master’s inner wisdom and Soul to the outside. Students learned these qualities not by reading a literal book, but by reading a Master. The Master was like the Seal pressed upon the Wax (his Apprentice).

It is interesting to question, ‘how are virtues taught?’ Many come to appreciate the opinion above. And although this view didn’t necessarily change, over time, as schools grew in size, the method of a Master’s communication needed to adapt. The attention given to each student by a Master couldn’t be provided as effectively for final result. As this became more of an issue, a physical master found transition into a textual master. Popular tales of the time encouraged the emulating of a master through text. Readers were believed able to recognize and develop esteemed qualities and become like the hero described in a story. (Stories of the Grail Quests come to my mind).

This is one reason why Rithmomachia grew in popularity as schools expanded. It was thought playing the game of Rithmomachia could teach the virtues of Masters. Virtues like patience, humility, respect, honesty, etc. were exercised in playing. It would also teach contemplation, appreciation, and wonder of number. Unseen values were experienced and attained through play of the game. Players challenged each other and witnessed Wisdom. Steel sharpens Steel.

Negative responses or vices were also taught to be controlled through game play, like anger, haste, or rudeness. The game continued to grow in respect because it provided the means to develop virtues and granted knowledge of the Divine to players. It was an extension of the University’s teachings.

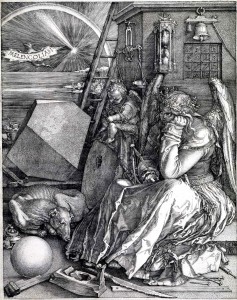

Albrecht Durer’s Ladder

Another aspect worth noting is The Philosopher’s Game was played to cure a person from melancholy. It was believed the rise of a person’s spirit through contemplation of number helped rid man of discord. In Albrecht Durer’s renowned Melencolia I work of 1514, a ladder is noticed rising out of the image. Ladders often represent the ascending levels of intellectual growth and spiritual enlightenment of man. Durer chose to display a cluster of buildings between the 3rd and 4th rung of his ladder and I’ve considered this as representation of a University where the Trivium (3/rhetoric, grammar and logic) and Quadrivium (4/studies mentioned above) were joined and devotedly taught.

The positioning of the University within the ladder is an intriguing addition to Durer’s impressive work. It offers admirers, who would have been prominent men of the time and most likely aware of The Philosopher’s Game, the opportunity to quietly acknowledge the importance of the Seven Liberal Arts and Sciences as a way to relieve Melancholy, and the means to give Harmony and Wisdom to man.

This acknowledgement for way to Wisdom is additionally seen within literary references; where Rithmomachia was commonly used as a symbol to represent the Quadrivium. One example is within the work of Honorius Augustodunensis entitled, De Animae Exsilio et Patria. Honorius shares the journey of a Soul from ignorance to wisdom by passing through ‘cities’ of learning. These ‘cities’ are the disciplines of the Trivium and Quadrivium. Honourius uses Rithmomachia to represent the city of Arithmetic and the door to the Quadrivium. Like symbolized by Durer’s ladder, the study of the Arts and Sciences was thought to be the way to discover the Divine.

I respected The Philosopher’s Game’s role in the importance of wisdom to be gained through the Seven Liberal Arts and Sciences. I liked how the game expressed a bond between a man’s learning to his leisure and how man’s instruction from books could be acted and improved upon through the game. I liked how contemplation of Boethian number led man to higher goals and visions of the Divine. These were well-established facts.

But by the late 1600’s, the applications and demands for study of number were changing. The teachings of the Universities needed to include more practical, calculable, and scientific understanding to Arithmetic. Boethian thought and the theological reflections of the Quadrivium were being cast to the wayside. Mathematics was evolving and The Philosopher’s Game was losing popularity. Although this is explainable in light of the incredible developments and modernizations happening in the time, I found it difficult to imagine that what was so favorably and greatly esteemed would be allowed to be totally forgotten.

Transition for Rithmomachia’s ideals

What I realized through study of The Philosopher’s Game was the teachings of the Universities not only educated man on practical matters, but were highly involved in developing a man’s moral character, virtuous nature, and Divine understanding. It was not merely Boethian mathematics being replaced and neglected, but the hidden prizes its contemplation transferred onto man. The belief for enriching the Man’s Soul through considerations of the Quadrivium was a treasured idea. I felt those who knew its secrets should want to find a way to continue its conveyance.

Much of the above was on my mind when I read the original and illuminating research shared by Duncan Burden on his Freemasonry website; HumbleMason. I was questioning the decline of The Philosopher’s Game, devoted to Boethian studies, and wondering did it fully disappear. Did the past veneration for the Seven Liberal Arts and Sciences, and what it imparted, simply vanish?

If you have read Burden’s work providing an excellent perspective on the importance of the Seven Liberal Arts and Sciences in Freemasonry, you might imagine my excitement. He shared how Apprentices into Freemasonry were encouraged to study the Liberal Arts. Through his research, he had even noticed a slight, but significant change of wording for this encouragement. As a man rose within the system, a Freemason was later ‘expected’ to study the Seven Liberal Arts and Sciences so that, and he quotes, “you may better be enabled to discharge your duties as a Mason and estimate the wonderful works of the almighty.”

I was thrilled. Here I was reading on Burden’s website how the Divine, through the Quadrivium, and absorption of its principles, was once again being introduced. Those most influential men, who studied the Arts and played The Philosopher’s Game, might not have let the prized beliefs become forever lost. Perhaps they had even discovered something more powerful to express. Could it be possible that those learned men of honored status realized Freemasonry could incorporate the game’s valued teachings within its system?

What the exact circumstances are may never be known. What I find so extraordinary, however, is that the quiet decline of Boethian teachings and play of the game coincides with the beginning murmurs of Freemasonry. This, and the fact they share one of the most remarkable and worthy purposes in a man’s life is amazing to consider. The Philosopher’s Game was revered for centuries for the further development of man through active participation, and when it vanished, Freemasonry stepped in and became known for doing the same. All had not been lost; whether intentional or not.

It truly was remarkable to me. I love collecting and researching ancient and old games, and Rithmomachia was always a favorite. This was partly because of the age it was played and the many threads of travel it led me on. But certainly, too, for what was believed learned through its play and its mysterious disappearance. I loved the quest given by the game and still do.

The Secret Star in Poussin’s Shepherds of Arcadia

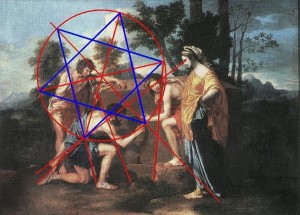

As Duncan Burden began to reveal more of his findings into possible deeper layers of Freemasonry, another circumstance caught my attention. Burden was relating a theory on how a geometric shape, a tilted hexagram, was hidden within paintings linked to the mystery of Rennes le Chateau; and to its Priest’s unexplainable riches and Freemasonry.

From my research into The Philosopher’s Game and realizing its dedication to Boethian thought, along with feeling Freemasonry incorporated its principles and beliefs, I found it curious that the tilted hexagram was formed by using the three primary shapes; circle, triangle, and square. These were the same shapes as the game pieces used by players to realize the Divine in the game. The shapes were unique to Rithmomachia. No other game used them. Now it is true, they are primary shapes, found in numerous ways, but as stated, this was not the only similarity between the Game/Boethian thought and Freemasonry.

The game promoted and encouraged man to reach and grow beyond their lower levels through the Seven Liberal Arts and Sciences. The game also advertised it could heal the mind, and lead players to see the Divine. Participation in discovering harmony was key. These chief objectives were shared in Freemasonry. And now an idea was being proposed by Burden that a secret star holds a vital meaning which included similar features to the game.

Interestingly enough, maybe coincidental (who’s to say), but the decoded message which hinted to this ‘Key (tilted hexagram)’ used a double chess board in its deciphering process. Rithmomachia was played on a double chess board using the very three shapes this Key was created by. I was amused.

I had talked with a friend on how I felt if the hexagrams were intentionally being drawn attention to, and I believed Burden had formed an impressive case for this, then surely the central points of these should have significance. I couldn’t imagine the central point wouldn’t have a hidden meaning itself; a point Burden had shown was shared by all three primary shapes to form the Star, and which was a point from which a Mason could not err.

If the central point could be found to hold a purposeful and secretive meaning, this would strongly support the finding of Burden’s hexagram, and obviously the hexagram supported the center point. Perhaps it was a secret meaning already known by Burden and within the realm of Freemasonry not publically shared.

I had taken note the center points of the two hexagrams shown by Burden to be on the Elbow of a shepherd in the Shepherds of Arcadia painting by Nicolas Poussin, and in the other on the Fingertip of the Teniers painting (the two paintings thought referred to in the deciphered message of the RLC parchments). Honestly, I thought quite ridiculous center points and disappointed, until I was reading one night (How Mathematics Happened by Peter Rudman) and came across a sentence which caused me to pause.

The sentence was, “The word cubit is derived from the Latin word for elbow and defines a measurement unit from the elbow to the fingertips….” Elbow, Fingertip? Cubit? First measure of God? I remembered the center points.

The cubit is one of the ‘first measures of God’ in the Bible. I wondered if maybe this wasn’t leading to a hidden understanding to the central points in the paintings. Word origins were important and studied in the past. It is not unreasonable at all to think Poussin would have known ‘Elbow’ could cleverly hint to ‘Cubit’ solely itself and be noticed by admirers of the Star. And the fact the hexagram in Teniers painting included its central point on a ‘fingertip’, and the Cubit was a measurement from Elbow to Fingertip added to my wonder.

Whoever wrote the coded parchment’s message, stating both paintings ‘held’ a Key, might have directed readers to these paintings for their particular hexagrams and centers for this reason. A secret understanding to the center of the three shapes, forming a hexagram, in Poussin’s painting (and Teniers) could be seen. I was in awe.

I loved the thought the Cubit, veiled by Poussin, to represent the Heart of God. God is known as the Grand Architect of the Universe, and the three primary shapes believed to be the foundation for all creation, sharing a common heart/center and forming the star, presents a powerful possibility. Wouldn’t the heart of God be the ‘first measure of God’? The same definition for Cubit. An ingenious play with words.

The painting by Poussin demonstrated the Creator by the inclusion of the Hexagram formed by the trinity of foundational shapes. The center point of Burden’s hexagram is also said to be the point of which a Mason cannot err. To me, this would be where man has discovered the heart or will of God and has gained Wisdom.

The Grand Architect of the Universe/God is often referred to as Love itself. Ephesians 3:18 says “…..and I pray that you, being rooted and established in love, may have the power, together with all the saints to grasp how wide and long and high and deep is the love of Christ, and to know this love that surpasses all knowledge that you may be filled to the measure of all the fullness of God.”

The belief God reveals himself to us through Geometry/number was deeply felt. Bernard of Clairvaux is famed for asking ‘What is God’ and answering ‘He is length, width, height, and depth.’ Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153) was an admired French Abbot and in 1830 earned the title Doctor of the Church for his widely respected thoughts and writings. He is known for his support of the Cistercian Order and the Knights Templar.

He stimulated thoughts that God could be realized by understanding mathematical patterns in all things. In Robert Lawlor’s Sacred Geometry, Lawlor shares how St. Bernard was instrumental in promoting pure form and inspired architecture to display God’s beauty and love. He includes the words of St. Bernard, “There must be no decoration, only proportion.” God could be known through our visual senses.

I was reminded by a passage I read in Michael Masi’s book mentioned above on Boethius and the Love which rules us all. And remember, this secret hexagram proposed by Burden was to be discovered through the understandings of the Seven Liberal Arts and Sciences and Boethius encompassed these Arts. The passage was:

“That the universe carries out its changing process in concord and with stable faith, that the conflicting seeds of things are held by everlasting law, that Phoebus in his golden chariot brings in the shining day, that the night, led by Hesperus, is ruled by Phoebe, that the greedy sea holds back his waves within lawful bounds, for they are not permitted to push back the unsettled earth- all this harmonious order of things is achieved by love which rules the earth and the seas, and commands the heavens.

But if love should slack the reins, all that is now joined in mutual love would wage continual war, and strive to tear apart the world which is now sustained in friendly concord by beautiful motion.

Love binds together people joined by a sacred bond; love binds sacred marriages by chaste affections; love makes the laws which join true friends. O how happy the human race would be, if the love which rules the heavens ruled also your souls.”

If the Geometric Shape, the hexagram, was concealed so onlookers could appreciate God in form, then wouldn’t the center point be God’s heart; the first royal measure; His love? The love which rules the heavens and our souls. This is concealed in Poussin’s work, and how powerful it is to recognize the heart of God.

Conclusion: The Hidden Prize

Duncan Burden generously shares his ideas for the inclusion of the Hexagram and background leading up to it. This all can be read more thoroughly on his site and I feel it offers a deeper level of appreciation for Freemasonry and its purpose. He offers extraordinary and unique perspectives not found anywhere else.

Through Burden’s research I gained a better understanding towards the Seven Liberal Arts and Sciences and was grateful for the connective work with The Philosopher’s Game and Boethian disciplines.

Games are overlooked keepers of knowledge, and I love the journey in studying them. I was thrilled the journey led me to feel Freemasonry was now the keeper of The Philosopher’s Game knowledge. Again, deliberately planned or not doesn’t really matter to me. I see the game’s purpose in Freemasonry and take comfort it isn’t lost.

I will end with what fascinates me most on The Philosopher’s Game purpose. For me it is to seek the Divine heart of God with sincere desire. I believe this can be done by contemplating number and realizing the underlying principles in Creation.

It is the opportunity to always seek and grow in this love. As stated by Bernard of Clairvaux this was the envy of angels. Bernard of Clairvaux said, “The best and most desirable is that ornament which even angels might envy.”

He was referring to how man is given the choice to become an admired piece of art, an ornament, a Master. That each of us has the ability to transform our selves. That a mind, body, and soul which receives the Divine within can reflect Divine character to all. Angels, without human body, do not have this opportunity to transform themselves into this ‘ornament’ and so might envy the shaping of man.

That is the hidden prize of The Philosopher’s Game.

Sources:

Parlett, David. The Oxford History of Board Games. Oxford University Press, 1999

Masi, Machael. Boethian Number Theroy. Amsterdam, 1976

Ferguson, Kitty. The Music of Pythagoras. Walker&Company, 2008

Jaeger, C. Stephen. The Envy of Angels. University of Pa Press, 1994

Finkel, IL, editor. Ancient Board Games in Perspective. British Museum Press, 2007

Moyer, Ann. The Philosopher’s Game. University of Michigan Press, 2001

Burden, Duncan. www.humblemason.com reviewed 2016

Wow! That was masterful. Thank you for sharing.

Thanks twingem…..I love researching games and believe a lot is hidden in them….. ~jenny

Hi Jenny,

Ccongratulations on the publication of your article. I am trying to get the background, before diving into it. I am unable to find the article, although I see one that looks related:

http://thehereticmagazine.com/issue-7/

http://thehereticmagazine.com/the-priceless-wisdom-in-the-book-of-games/

Is this an update to the November 2015 article, or is there another one? I notice Issue 9 seems to be the current issue.

astree

Hi astree, the above is the article from issue 7 and is a stand alone. (I suppose I used the word Hidden and not Sacred–but it is both…lol)

The other article is a stand alone too. That I wrote for the blog page of The Heretic and share my thoughts and findings from the 1283 Book of Games.

And thank you…….. as I mentioned to twingem…..and as some might know, I collect antique games and love to study them. There is a lot of symbolism to be discovered in their play. I love it! ~ jenny

Fascinating! I’ve studied a little bit about the often sacred and hidden meanings behind games (nowhere to the extent you have), this article was most enlightening. I’d never heard of the Philosopher’s Game, but will definitely look into it now. I wonder if that game was one of the inspirations for Hermann Hesse’s «Glass Bead Game»? I’ve followed a few people’s attempts at “recreating” the game from Hesse’s novel, and the Philosopher’s Game sounds like a perfect starting point!

Thanks for the reminder about that book, Greg. I haven’t read it yet, but have it on my list/stack to. I think I just might pull that out tonight and have a read…..

Thanks!

The hexagram represents the tree of life, and the centre point of the hexagram represents the hidden sphere in the tree of life, sometimes called “the Abyss”. So it’s true that the centre of the hexagram is pretty important.

Reading this article, I can’t help but be reminded of the Zen saying: “When the finger points to the moon, the fool looks at the finger.” Surely, if the fingertip seems to be a focal point in the sacred geometry of a painting, you are meant to look where the finger is pointing? And even following the finger can be a fool’s errand. You are meant to look at what the overall sacred geometry is.

I hope you were able to dive into the Glass Bead Game. I too believe it has roots in the Philosopher Game. The book definitley makse much more sense now with an understanding of the Philosophers Game. I have a book on the Quadrivium and think I might crack it open today.