Guest Post by Duncan Burden

The Ring of Gyges – The Lord of Rings

The pun in the title is intended, as the legend of the Ring of Gyges surely must be the Lord of all Rings, as not only is it one of the earliest ring of power stories, but it is the root of many of the stories that came later, including Tolkien’s own ‘Lord of the Rings’.

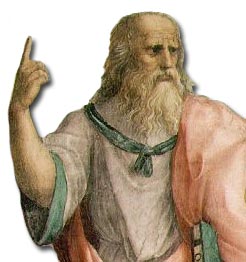

The story begins with the ancient Greek Philosopher, Plato, and the second book of his ‘Republic’.

What should be understood is how Plato, as did many Greek Philosophers, wrote. The most common tool an ancient writer would use to try and express their philosophical arguments is to use stories to help the reader to understand a principle either by creating a direct metaphor/allegory for the audience to engage with the concept.

For example, Plato once wanted to explain the problem of Philosophers trying to teach the populous of his time, but rather than explain it, he wrote the ‘The Allegory of the Cave’. He structured the text as if it was the famous Socrates telling the story to Plato’s own brother Glaucon, with Socrates telling a story of a group of prisoners stuck in a cave, with all their knowledge of the world outside being drawn from shadows on the wall.

As this is all they had, they named and established their own understanding of the world purely on these images. Eventually one group escaped and discovered the world was not as they had imaged and returned to tell the others the truth. But now those still trapped in the cave had become so limited and entrenched in their opinion, they could not even conceive all that their friend was trying to explain, and so denied what the individual was saying.

This was an allegory, which itself is a classical expected way to explain an idea, that using a story is an easy and simple way for an audience to engage with what an individual wants to convey. In this case, the idea that the ancient Greek populous was so entrenched in their myths and legends about life and creation, they could not appreciate the knowledge of the new philosophers.

Such is Plato’s story of the Ring of Gyges, where he has Glaucon embellishing on the little known history of Gyges of Lydia, who was actually a historical king and founder of the Mermnad dynasty. Different accounts of his rise to power are given, but all are based on the concept that he was originally just a subordinate of King Candaules of Lydia, and seized the throne by murdering him, with rumours of also seducing the Queen and later marrying her.

Plato has his brother introduce the story by saying the ring was found by a shepherd, who discovered a newly exposed cave in a mountainside. In the cave was a tomb with a bronze horse containing the dead body of a huge man who had the golden ring on his finger.

The peasant soon discovered that the ring could turn him invisible if he turned it one way on his finger and visible again when he turned it the other. The character used this power to get in favour with his king, the King of Lydia, but then also used the ring to seduce the king’s wife and eventually killed the king and took the kingdom. Thus the story of Gyges of Lydia’s rise to power is used to create an allegory for Plato.

Plato uses this tale to set the scene of an argument in ethics, to present the question that why should we do right if we can get away with doing wrong? This premise of how a morally average man could be challenged with the gift of invisibility is actually the origin of H. G. Well’s ‘The Invisible Man’, but the concept of invisibility is meant simply to convey the idea of what if you could be assured with getting away with something, would they still be moral and not do it, but being assured we could not get caught, would we do it. Thus, is morality just a value against ‘judgement’ rather than self-respect?

So, do we consider the ring to exist? Why not? Plato’s use of allegory is how the idea of Atlantis came into reality, and many are seeking and claim to have found that lost land. Yet, real or not, Plato’s beautiful question on ethics is real, does immunity create corruption?

This notion of power of immunity creating corruption in an individual obviously echoes J. R. R. Tolkein’s ‘One Ring’. If anything, Plato’s Ring of Gyges has forged more than one ring legend, and rules the notion of many stories, as Peter Jackson’s Gandalf said…

‘There are many magic rings in the world, and none of them should be used lightly’, ‘The Fellowship of the Ring’ 2001

~Guest Post by Duncan Burden

If a person weren’t green with envy, maybe they wouldn’t be tempted by “invisibility” to do wrong. One curse often feeds another.

The fruit does not fall far from the tree, why must I carry those curse’s. Yes, Immunity does create corruption so immunity can be feed.

Yet, without the curses how could we ever be judged?

It’s not a question of the missteps, it’s about the path’s coarse.

Cant help to think that the origins of such tales of morality spring from the same fountain –or even give rise– to such concepts of “karma” and “justice”.

Its so nice to be reminded that the trail of the shepherd at the tomb leads all the way back to Plato (with the corpus of giant in there no less!)

Hayward, I think it goes way back before that. The development of written languages (even glyphs before) simply allowed the concepts to be put down for future reference.

After all, how could religious concepts happen without recognizing some form of these ideas? Or for that matter, what about community?

It makes you wonder where in evolution these thoughts start, and I think it started well before our homo sapiens status.

Hi Buckeye- I appreciate the sentiment but I wasnt really considering the actual origins of such archetypes literally per se, more so how the thought surroundung such concepts evolved. The moral tale about the potential corruption that might befall the person who no longer is limited by the same laws that govern others (immunity) has an equal correspondant with the ideas behind Karma (not as retribution, but in the sense of a natural law od cause and effect) as well as the idea of justice (as in the sense of bringing counterbalance to the unven weight of the scales). These are just two other principles which I think have deep and related value particularly as concepts expressing morals and ethics, even historically.

Furthermore, I wouldn’t even begin to attempt a first cause discussion out of this thread :).