One of the great mysteries of antiquity has been the “lost” tomb of Alexander the Great. To this day, no one is certain of its location, although multiple theories abound. There are claims to its location in modern Alexandria, there are some who say they have found it in eastern Egypt and some have even “discovered” it in northern Greece. In 2004, The Egyptian Antiquities Organization had officially recognized there had been more than 140 searches for Alexander’s tomb in Egypt alone. So far, none of these discoveries have yet proven to be conclusive.

One of the great mysteries of antiquity has been the “lost” tomb of Alexander the Great. To this day, no one is certain of its location, although multiple theories abound. There are claims to its location in modern Alexandria, there are some who say they have found it in eastern Egypt and some have even “discovered” it in northern Greece. In 2004, The Egyptian Antiquities Organization had officially recognized there had been more than 140 searches for Alexander’s tomb in Egypt alone. So far, none of these discoveries have yet proven to be conclusive.

One of the more compelling stories that has emerged however, comes from one researcher who has historically traced the remains of Alexander to – of all places- the cathedral of St. Mark’s in Venice. The trail of evidence mapping how this ancient Macedonian king could have wound up in a Catholic church in Venice is a very unlikely story of mixed identity, yet one that is acutely pieced together by archaeologist and historian Andrew Chugg.

As the background of the story goes, during Alexander the Great’s military campaign into Babylon (present day Iraq), Alexander had fallen ill suddenly and died. Whether his death had been by typhoid fever or by poisoning no one knows, but historic accounts indicate that after his death, his body had in some way been preserved for two years prior to being sent back to Alexander’s homeland of Macedonia. Even though being buried in Macedonia was apparently against his wish (Alexander had allegedly asked to be deposited into a river or oasis in Siwa) as his body was en route to Macedonia, his general Ptolemy I Soter intercepted the funeral carriage and carted off with the body to Memphis, Egypt. In Memphis it is assumed that his body was placed inside of a tomb where it supposedly laid for a couple of decades.

After some time (and apparently by approval of an oracle from the local serapeum temple) Alexander’s body was eventually transferred to Alexandria, the capital of the empire, at the behest of Ptolemy Philadelphus in 280 BC. Sometime around the year 274 BC, the body of Alexander was eventually housed in a mausoleum containing the remains of other dynastic figures as well. It is at this location where many historic records account to its location existing at the intersection of a major north-south and east-west crossroads in Alexandria.

Several well-known historic figures had visited the tomb of Alexander at this location in Alexandria. Julius Caesar, Cleopatra, Augustus, Caligula, Hadrian, Severus and Caracalla. Caesar visited the tomb and paid respects to his “idol” in 45 BC. Cleopatra allegedly took gold from his tomb sometime during the 4th decade BC, to finance her war against Octavius. Octavius/Augustus offered flowers and a diadem to the tomb and body of Alexander shortly after Cleopatra’s suicide in 30BC. Caligula stole Alexander’s breastplate and wore it while parading around Rome, according to Suetonius, in 2 AD. Severus sealed up Alexander’s tomb in the early 3rd cent. AD to prevent any further mishandling. Finally, Caracalla took Alexander’s tunic, ring and belt sometime in 3 AD.

“Tetradrachm of Lysimachus” minted at Lampsakos c. 305-281BC)

At this point in history, Alexander had already evolved into a mythical figure. The fact that few Roman emperors considered themselves to be reincarnations of Alexander (including Caligula and Caracalla) should stand as testimony to the god-like status that had been achieved by his legacy. Alexander himself had in fact, even considered himself to be the son of Zeus. In addition to this, he had been accepted as the divine ruler of Egypt, as pharaoh. Over the centuries, multiple works in stone of Alexander have been uncovered, depicting him as kosmokrator (creator of the universe), as Hercules, as Pharoah in hieroglyphic form, as the sun god Helios and Ra. Coins even depict Alexander with horns, in the guise of Ammon-Zeus.

There is much available to support a conclusion along these lines, that many believed Alexander was not merely mortal (and just as Alexander had perhaps himself seen fit), but was in fact, a God. For this reason, his tomb in Alexandria must have stood not simply as a memorial to the great king, but potentially as a place of worship and offering. It is within this pagan context surrounding the admonishment of Alexander that we begin to lose track of his location.

The historic records attesting to the presence of Alexander’s tomb at Alexandria extend up until approximately 391AD, when the last known mention is made by Libanius of Antioch. In his public oration to Theodosius I, To the Emperor of City Councils, Libanius makes mention of Alexander’s corpse being displayed in Alexandria while professing grievance about the looting of public tombs and temples by local officials of the time. There is no further mention about the location of the tomb of Alexander in history.

The end of the 4th century AD in the Roman Empire was notably troublesome for pagans. The Christian persecution of paganism under Theodosius I began in 381. Visits to the temples were forbidden, pagan holidays were abolished and practice of pagan rituals were punishable by death. This decree swept the breadth of the Roman Empire, wherein Theodosius’s decree became responsible for the destruction of many temples, holy sites, and the looting of images and objects of pagan veneration. It is during this time that the tomb of Alexander becomes lost to history.

Not too shortly after however, another tomb appears for the first time in historic record, in Alexandria. It is the tomb of St. Mark.

The first historic accounts of the burial of St. Mark having a location in Alexandria date to the period directly surrounding the last decade of the late 4th cent. AD. In the Lausiac History of Palladius, there is mention of a pilgrimage to the “Martyrion of Mark at Alexandria”. In 392 AD, St. Jerome states in his De Viris Illustribus that St. Mark’s body is buried in Alexandria, which becomes the first mention of an historic location for St. Mark, even though he had died much earlier, in 68. AD. Despite some possibility that the tomb of St. Mark had somehow gone undetected until the late 4th cent. AD, it has widely been reported in record that after facing execution, the body of St. Mark had been burned anyhow, which means his body would have been reduced to ashes.

So who was it that was actually buried in that tomb at this point in history? Was it Alexander all along, who’s tomb had been conveniently converted into a Christian holy site instead? If Alexander had been transported somewhere else, why is there no historic account for such a thing? As to an answer, history leaves us no clue. That is, until perhaps the 9th cent AD, when the next chapter of this particular story takes place.

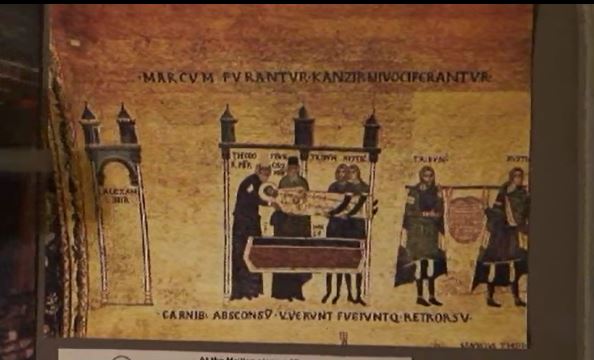

In 828 AD, two Venetian merchants with the help of two Greek monks travel to Alexandria to retrieve holy relics for the erecting of a new church in Venice dedicated to St. Mark. Alexandria is now controlled by the Islamic Abbasid Caliphate at this point. As the story continues, the merchants, with the help of the monks, stole relics and the bodily remains of St. Mark and sneaked them onto their shipping vessels hiding them under several layers of pork to disguise them from the Muslim authorities. This story is allegedly illustrated in mosaic at the cathedral of St. Mark itself.

cathedral in the chapel of St. Clemente, in Venice)

Here we see the depiction of the monks with the merchants at Alexandria removing the body from a coffin and carrying it away in a basket. The first question which might arise in response the mosaic is, if the body of St. Mark had been recorded in history as being burned, why is it being depicted here as a full body? While this image should by no means should read as a literal account, it does make one consider the details.

But are there any other details that might identify the body which was deposited in St. Marks in Venice?

Moving up to more recent history, in 1960, a fragment of sculpture was discovered embedded in the foundations of the cathedral, under the church’s main apse. This fragment was identified by Eugenio Polito (an expert on Greek and Roman armaments) in 1998 as being a component from a Macedonian tomb dating to the 3rd cent. BC.

Depicted in this sculpture are several articles that identify with Macedonian tomb motifs of the era. First is the shield portrayed in the image, which can be automatically connected to the “Star of Vergina”, the well-known emblem of the Macedonian kingdom. Next is the dagger hanging on the left side of the object, known as a “Kopis Sword”. Other elements included warrior greaves (shin guards) and a what has been identified as a Sarissa spear.

The stone of the fragment has been identified as Late Cretaceous limestone with rudist fossil, but there are sources available for this throughout the Mediterranean. Some prominent locations include both a Roman-era quarry at Aurisina near Trieste (70 miles near Venice) and another near the Nile at Abu Roash in Egypt (about 100 miles south of Alexandria). At Abut Roash, there is a site known as the “Lost Pyramid” (the Pyramid of Djedefre) which is an ancient pyramid structure that had been standing prior to the arrival of the Ptolemic and Roman rulers, who had dismantled the structure and used it as a quarry to build its cities.

Is it possible that the ancient Ptolemic rulers used some of this stone to build the Alexander’s mausoleum in Alexandria? Possibly. But although the possibility exists, it does not mean the theory is conclusive.

But even if were so, what would the fragment tell us? Are we to believe that this item might have been carted off from Alexandria along with the remains of a “mistaken” St. Mark –who was actually Alexander the Great? Is it possible that it came from somewhere else? In either case, why would a relic which could only been made for a Macedonian “noble” be brought and deposited in the foundations of a Catholic cathedral in another region in the first place

Perhaps the best way to validate the body at St. Marks would be a visual inspection of the remains themselves. One would be able to see if in fact the remains were burned, which would correlate with the account of St. Mark. If not, the next would be to inspect the bones.

It was recorded that Alexander received certain wounds in battle. If such wounds could be identified on the bones that matched the historic descriptions, it would seem almost undeniable. But so far, the Church authorities refuse such an inspection. Until then, it looks like the search continues.

This is fascinating, Hayward. Such a mystery! You shared an incredible possibility for where Alexander’s lost tomb/remains could be. Thanks so much. I’ve ordered the book, and as you mentioned, would love to do a Six Questions with Andrew. We’ll see!

It would be great to hear if anything new has come to light since his original research. Hope it can happen.

Thanks!

Thanks Nate- Well, to be fair to the authorities of the church, its not as if they can just open things up and allow anyone to start digging through their crypts without due cause. But of course on the other hand there is absolutely zero incentive for them to prove who’s the remains actually are.

Apparently the Church is resting on an explanation that, when the remains were moved from one section beneath the church to another to protect it from frequent flooding, the investigator in charge at the time confirmed through a deposited lead tablet that the remains were identified as St. Mark. This however, does nothing to explain the historic account that St. Mark was burned in 1 AD. The plot thickens with a written tradition from the Passio of St. Peter supposedly from the 4th/5th century AD which claims that St. Mark’s body was taken out of the flames by his followers. Apparently though, this account has been widely accepted as the invention of a later hagiographer from 6 AD.

In any event, the historic accounts do not seem to bode well in supporting the idea that St. Mark (who seems to appear out of nowhere in 4AD after being burned in 1AD) is the likely identity of those remains and that actually (unfortunately) it supports more the possibility that these items have been forged.

Very interesting article however, there is some information I came across which may disprove the Venice theory.

Some time ago I came across information about Julius Ceasar’s visit to the resting place of Alexander. Apparently, Caesar wept laying eyes on Alexander’s preservered body. Apparently, Alexander was submerged in honey which acted as a preserver and preventing the decomposing of the remains. Caesar wept because Alexander conquered more land than Caesar at half his age and thus could not beat his conquests. Caesar leant over the body to kiss Alexander on the lips but his nose accidentally brushed against Alexander’s nose which broke off. If this is factual, Alexander’s remains were so fragile, it would not survive intact on its journey to Venice particularly if it was hidden under loads of pork.