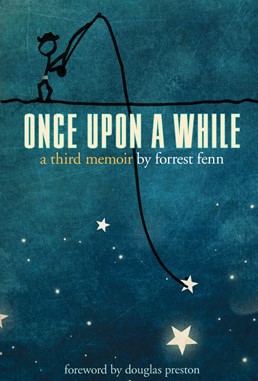

Forrest so generously shared the Foreword by Douglas Preston for his NEW Book, Once Upon a While, with me.

He said I could post it if I wanted to. I said, OF COURSE! 🙂 Here is the Foreword:

Treasure of Another Kind

By Douglas Preston

I first met Forrest Fenn in the Dragon Room of the Pink Adobe in the late 1980s, where he habitually occupied a table in the corner, which featured a rotating cast of eclectic Santa Feans, including John Ehrlichman, Larry Hagman, Clifford Irving, Ali MacGraw, and Rosalea Murphy. I joined the table as a young, unknown, and struggling writer, wondering how the mistake had been made inviting me among all these famous people. But Forrest Fenn was an outstanding lunch companion, telling story after story that kept the table enthralled, and we instantly hit it off.

That was the beginning of my friendship with Forrest, who is one of the most remarkable people I have ever met. Here is a man who came from a small town in Texas, barely graduated from high school, spent 20 years in the Air Force as a fighter pilot, flew 328 combat missions in Vietnam over a period of 348 days, survived being shot down twice, and was awarded a raft of medals; he then retired, moved to Santa Fe, and built a world-famous gallery that put Santa Fe on the art-world map; he ran the gallery for 18 years with his wife Peggy and together they raised a wonderful family. Along the way he also published 10 books (this is the 11th), acquired and partially excavated a 5,000 room prehistoric Indian pueblo, and amassed a peerless collection of Native American antiquities and art.

I knew I was a friend of Forrest’s when, in the early 1990s, he invited me into his vault. This walk-in fortified room, hidden in the back of a closet, was filled with extraordinary treasures—Pre-Columbian gold artifacts, Indian peace medals, a Ghost Dance shirt, the greatest collection of Clovis points in existence, and (later) Sitting Bull’s celebrated peace pipe. Forrest had been a dealer in art and antiquities for years, with many superb objects passing through his hands. These were the things he had kept, the best of the best. Forrest liked artifacts that told stories, and each one had a rich and fabulous history.

In that first visit to the vault, Forrest wanted to show me something quite specific. He explained that he had been diagnosed with cancer. Although it was in remission, the prognosis was not good. He did not, he said, wish to linger in weakness and pain, and he especially did not want to put his family through a long and difficult ordeal as he wasted away from cancer. The honorable and dignified solution for all concerned, he told me, was to end it quickly and cleanly, by suicide.

But Forrest is a complicated human being, and with him nothing is simple. He had worked out a plan to end his life that would, he hoped, give something back to the world and encourage people to explore the outdoors he loved, while at the same time generating high interest, if not consternation. Forrest was never one to shy away from causing a stir.

On the right side of the vault, on a sturdy shelf, sat a bronze casket of ancient workmanship that he had recently acquired. Gene Thaw, the noted collector, had identified it as a rare Romanesque lock-box dating back to 1150 A.D. He opened the lid to reveal a dazzling heap of gold—monstrous nuggets, gold coins, Pre-Columbian gold objects—along with loose gemstones, carved necklaces, and a packet of thousand and five hundred dollar bills.

“Go ahead,” he said, “pick up a nugget.”

I reached in and picked up a massive raw nugget the size of a hen’s egg, cold and heavy. There is something atavistic about gold that thrills the imagination, and as I hefted it I felt my pulse quicken.

“That’s from the Yukon,” he said. “Nuggets that large are rare, worth three to four times their bullion value.”

He reached in and removed the bills.

“What are those? Funny money?”

“No. It’s legal United States tender”—not normally used in circulation, he said, but sometimes these large denomination notes were exchanged between banks to keep their accounts in balance. It wasn’t hard to obtain one; he simply called his bank and ordered it, and a week later it arrived. He tucked the packet back in the chest. The chest also included a vital piece of paper which he showed me: an IOU for $100,000 drawn on his bank, so that he would know the chest was found when the discoverer collected the IOU. He rummaged around in the chest and brought out a handful of gold coins—beautiful old St. Gaudens double eagle gold pieces, along with dazzling gemstones, a 17th century Spanish emerald, and a gold Inca frog.

“Lift the chest. See how heavy it is.”

I grasped it by the sides and could lift it only with difficulty. The total weight of gold and chest was more than forty pounds.

Forrest then explained what it was all about. After his cancer diagnosis, he had begun thinking of his own mortality. The doctors told him there was an eighty percent chance the cancer would return and kill him. So he had worked out a plan: when the cancer came back, he would travel to a secret place he had identified and bring with him the treasure chest. In that place he would conceal himself and the treasure, and then and there end his life. He would leave behind a poem containing clues to where he was interred with the chest. Whoever was clever enough to figure out the poem and find his grave was welcome to rob it and take the treasure for themselves.

The final clue, he said, would be where they found his car: in the parking lot of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science.

He had worked out all the logistics but one: how he could pull this off by himself, without help. He did not feel he could entrust anyone else to assist him. “Two people can keep a secret,” he said, “only if one of them is dead.” He had already written the poem, and he now brought it out and read it to me. It was similar to the poem he later published in his book, The Thrill of the Chase, but not, if I recollect, exactly the same. He tweaked it many times over the years, making it harder.

I said that there were a lot of smart people out there and I feared the poem would be deciphered quickly and the treasure found in a week. But he assured me that the poem, while absolutely reliable if the nine clues were followed in order, was extremely difficult to interpret—so tricky that he wouldn’t be surprised if it took nine hundred years before someone cracked it.

When first I heard his plan, I was astonished and amazed. I didn’t really believe it. But the more time I spent with Forrest, the more I realized he was dead serious—no pun intended. I also realized it would make a marvelous movie: the story of a wealthy man who did take it with him. I pitched the idea to Lynda Obst, a classmate of mine from Pomona College, who had become a hugely successful Hollywood producer (Flashdance, Contact, Sleepless in Seattle). She loved the idea and asked me to write a treatment. When I called Forrest to make sure this was okay and offered to share the proceeds, he gave me his blessing, generously and firmly refused to accept any money, and made me promise only to invite him to the premiere—and the Oscars, if it got that far. I wrote a treatment and sold it to Lynda Obst Productions and 20th Century Fox. While the movie was never made (option available!) I did write a novel based on the idea, called The Codex, which featured a wealthy Santa Fe art dealer and collector who is dying of cancer and decides to take his fortune with him. He buries himself and his fabulous wealth in a secret tomb at the farthest ends of the earth, and he issues a challenge to his three lazy, no-good sons: if they want their inheritance, they have to find his tomb—and rob it.

As the years went by, I visited Forrest many times and saw the treasure in his vault. He often took things out and put other things in; he removed the currency, fearing it might rot; and he swapped out some of the gems for more gold coins and ancient Chinese jade faces. He also took out the IOU, he said, “because I thought my bank might not still be there when the chest was found.” He had worked out a better way, he told me, to know when the treasure is discovered, but he has not shared that secret with me.

And then finally, one lovely summer day in August 2010, I visited him and he brought me into the vault. The chest was gone! “I finally hid it,” he said. He was about to turn eighty years old and still in excellent health with no sign of cancer, and he decided to stop waiting and hide the chest now. This way was better, because he would be around to appreciate and enjoy the ensuing hunt.

And that, as everyone knows, was the beginning of what has developed into possibly the greatest treasure hunt of the 21st century. As I write this, seven of those nine hundred years have passed, a hundred thousand people have looked for the treasure, and three have lost their lives in the search—and yet it still remains out there somewhere, secreted in a dark and wild place, waiting to be found.

This treasure story is emblematic of who Forrest is—a war hero, a man of great generosity, and a truly original human being who lives life to the fullest, does things his own way, and doesn’t worry too much about what others might think. Forrest is, above all, a creator and a teller of amazing stories. In this book he tells thirty nine of the best of those stories, all true, with a note of commentary at the end of each one. They run the gamut from the inspiring and philosophical to the amusing and fabulous. These stories are a treasure of another kind, and some of them—who knows?— may contain more clues to the location of the real treasure.

I have read these stories with enormous pleasure, interest and enlightenment, and I hope you will enjoy them too.

,