(I had the opportunity to interview Brent Landau in 2016. The interview was posted on another website at the time, but I’m reposting it here for MW readers. Enjoy!)

MW  Questions Brent Landau: Author of The Revelation of the Magi

Questions Brent Landau: Author of The Revelation of the Magi

A few years ago I had the chance to read The Revelation of the Magi by Brent Landau, and thought it to be an absolutely enlightening story. The book was excellently researched and presented an astonishing tale. I’m so excited for this opportunity now to chat more with Brent on his impressive book and work.

Brent received his Th.D and M.Div from Harvard University, and a B.A. in Religious Studies from the University of Iowa. Currently he is a lecturer in Religious Studies at the University of Texas in Austin. Here he focuses his attention on the New Testament and early Christian writings, with a particular interest in apocryphal and canonical stories about Jesus’ birth.

His expertise on these interests is apparent. And unlike some scholars who seem unreceptive to contradictory stories to religious belief, he seems to welcome them, as clues to Truth might be found in all of them. The knowledge he has to share is immense, and so let’s get asking him some questions!

Questions with Brent Landau:

- 1) What a truly remarkable and fascinating book, The Revelation of the Magi, is, Brent! Thank you for publishing such an illuminating story. It is incredible to think a tale, holding rich, expansive, and extraordinary events relating to the Star of Bethlehem and on the Magi, could be pushed to the wayside for so long. What brought your attention to this ancient text? And were you surprised by its lack of study and consideration?

Thank you for your very kind words about The Revelation of the Magi, Jenny. I frequently continue to be amazed that such a rich text existed without receiving much attention, and that I was lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time to work on it.

I had been interested in the stories of Jesus’ birth since I was a kid, but when I was doing my doctoral work at Harvard, I knew that I wanted to do my dissertation on some apocryphal Christian writing about Jesus’ birth or childhood. When I went on a study trip to Italy as a doctoral student, I was blown away by how much the Magi were showing up in artistic representations, and I decided to investigate whether there were any apocryphal writings focused on them. After a bit of digging, I learned about the Revelation of the Magi through an article in an obscure publication. It sounded absolutely fascinating, and what was more, it happened to be preserved in a little-known language, Syriac, that I had just finished my first year of at Harvard. So I was in a perfect position to get to work on it right away.

Yes, I was definitely surprised by the fact that this text had received so little attention. It was so obscure that even my dissertation advisor at Harvard, who was one of the world’s greatest experts on apocryphal literature, had never heard of it. But the neglect was understandable for several reasons. First, apocryphal writings tend to receive much less attention than canonical writings in general. Second, stories about Jesus’ birth, both canonical and apocryphal, tend to be neglected in favor of materials about the adult Jesus (despite the fact that Christmas is so popular). Third, there aren’t that many specialists in apocryphal literature who know Syriac, so the number of people who were interested in and able to work on a text like this were rather limited from the start.

- 2) Although you were the first to translate this ancient Syriac text into English, is there evidence, say through paintings, mosaics, etc., to acknowledge the text (or translations of it) was known, read, possibly revered, in other parts of the world? If so, what time period do you feel the text had captured the most attention, and with who or where? If not, why do you feel it had been forgotten?

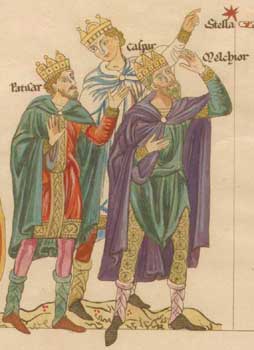

The reception history (that is, what people did with the text after it was written) of the Revelation of the Magi is fascinating. We don’t know much about how big an impact the text had in the Syriac Church, but a summary of the text found its way into a commentary on the Gospel of Matthew that was attributed to John Chrysostom, a famous ancient Christian writer. From there, it got included in a medieval compendium of Christian legends known as the Golden Legend that was very well-known throughout Europe.

Thanks to its inclusion in the Golden Legend, knowledge of the RevMagi became quite widespread. Thomas Aquinas refers to it, its narrative shows up in several illuminated manuscripts and painting from the Middle Ages (plates of which can be found in my book), and several early explorers of the Americas speculated that the indigenous peoples they encountered might have been the descendants of the Magi that the Apostle Thomas baptized (which is a clear reference to the plot of the RevMagi). I haven’t yet managed to figure out how and why the text vanished into obscurity again, but my guess would be that it had something to do with the Protestant Reformation, during which there was a reaction against many noncanonical writings that Christians had previously esteemed.

- 3) What did you find most interesting or revealing when reading the narrative of the Magi? And what do you feel is most important to understand and take from such a work?

There are three things about the text that stand out most prominently. First, it’s by far the most complex and elaborate expansion of the Magi story from Matthew’s Gospel. Lots of Christians were very interested in who these figures were, but the RevMagi is the one text that has placed them at the center of a grand and imaginative narrative.

Second, it is unique among ancient Christian speculation about the Star of Bethlehem. There were many theories going around in antiquity about what the Star of Bethlehem might have been, but the RevMagi is the only text to say that the Star of Bethlehem does not simply lead the Magi to Christ, but is in fact Christ himself in celestial form – that Christ is capable of transforming his appearance at will.

The third interesting aspect builds off of this idea of Christ and the Star being the same thing. There are a number of passages in the RevMagi that suggest that Christ’s ability to transform himself at will means that he can – and did – appear to people in lots of different places and different times. In fact, there’s one really rich statement Christ makes in 13:11 where he says that he has come to fulfill everything that was spoken about him throughout the entire world. If you put these passages together, it seems as if the RevMagi is saying that Christ is actually the underpinning of all of humanity’s religious revelations. This is a much more tolerant attitude toward religious diversity than we see in most early Christian texts, which usually present the gods of non-Christians as either completely imaginary or as actually demons. The RevMagi instead suggests that they are all products of Christ’s revelation to humanity.

- 4) As an expert on Infancy Texts, you’ve questioned the historicity of the Christmas Story and provided reasons for why it might not be fully accurate. Would you mind sharing some brief thoughts on these, and why writers of the time might have felt the need to create a tale, if not factual.

There are a few reasons that scholars don’t regard the infancy narratives as historically accurate. One of them is that there are no infancy stories about Jesus in our earliest Christian writings. The Gospel of Mark is the earliest gospel, and it begins with Jesus’ baptism. The sayings gospel Q, which was used by both Matthew and Luke, doesn’t seem to have contained any birth stories. And the writings of the Apostle Paul, whose letters are the earliest Christian texts we possess, say almost nothing about Jesus’ birth.

A second reason is that the two gospels that do contain stories about Jesus’ birth, Matthew and Luke, tell almost totally different stories with very few points of overlap. Both of them say Jesus was born in Bethlehem and grew up in Nazareth, but their explanations for why this takes place are totally different. According to Luke, Mary and Joseph live in Nazareth, go to Bethlehem for the census, during which Jesus is born, and then return back to Nazareth. But Matthew seems to think that they lived in Bethlehem, and that they only leave Bethlehem because King Herod is trying to kill Jesus; they then resettle in Nazareth after Herod dies and his son takes over. So they provide totally different explanations of the Bethlehem-Nazareth situation.

A third reason is that there are a number of details in the infancy narrative that seem very suspect historically. The best example of these is Luke’s census. The Roman Empire never took censuses of the entire Empire at once, and they never would have made everyone go back to their ancestral homes to pay their taxes. The Romans were at least nice enough to come to your village to collect money from you. All in all, there are multiple layers of historical difficulty with the infancy narratives.

Okay, so if they are almost entirely made up, then why did Matthew and Luke create these stories about Jesus’ birth? The short answer is that Christians had come to the conclusion very soon after Jesus’ death that he was, in some sense, the “Son of God.” They didn’t all mean the same thing by that, and I strongly recommend reading Bart Ehrman’s How Jesus Became God if this question is of interest to you. But some of them meant that Jesus had always been God’s Son, from the moment of his conception or even earlier.

If you came to the conclusion that Jesus was the Son of God from the very beginning (as opposed to being “adopted” by God at a later point), then it would be natural that you would want to explain the circumstances of how his birth took place, and how he was marked out as special even before his birth. In addition, there was an expectation in the Greco-Roman world that extraordinary individuals showed evidence of this even very early in their lives: people told stories about the birth of Plato, Alexander the Great, and the Emperor Augustus. So it “fit” the culture of the time for people to start telling stories – fictional ones, to be sure – about Jesus’ beginnings.

- 5) I appreciated your caution of saying ‘excluded texts of the Bible’ in one of the many interviews you have participated in, as it is not factually known why some texts weren’t ‘included’, and may not have necessarily been ‘excluded’ in the connotation the term infers. Your recent work entitled, New Testament Apocrypha, offering a wider range of material towards Christian thought and perspectives, provides some of these texts. But may I ask, why do you feel they weren’t included; was the Bible getting too big, or was it in effort to control and sway belief for the times? And how has your continued study on apocryphal texts affected your perspective on Religion and the various ways it might seek to regulate, if it does?

You’re absolutely right that we don’t know for certain why certain texts made it into the New Testament and others didn’t. It’s a very complex historical question. Two things are really important to keep in mind, however. First, many of the books that made it into our New Testament canon are extremely old. The letters of Paul are the earliest Christian writings we have, and they seem to be the first part of the New Testament that was gathered together into a collection.

Moreover, the four gospels that made it into the New Testament happen to be most of the very earliest gospels we know to have existed. The sayings gospel Q is probably the only gospel that we can say with certainty was as old as the canonical gospels and was not included – the Gospel of Thomas may be nearly this old, but this is a controversial and difficult issue to resolve. Other than these two exceptions, we have almost no evidence of other gospels that existed this early. So the first point is that the writings that form the heart of our present-day New Testament are exceptionally early, and I think Christians in the second century who started wondering about texts that should be in and out probably had enough institutional memory to know that these writings had been circulating in the churches for a long time.

Second, though, there were some ways in which certain kinds of writings were favored over others. The best example of this is how the four gospels that we ended up with are all narrative gospels. Collections of Jesus’ sayings didn’t make it in, except when they were incorporated as part of narrative gospels (as Q was). And when you look at Jesus’ sayings in isolation from the narratives in which they are (artificially) embedded, there are a lot of strange sayings. So I think that the sayings were “domesticated” in this way. The Gospel of Thomas says that it’s up to the individuals to find the meaning of its sayings, and I think there were probably a lot of early Christian leaders who thought that allowed for way too much freedom.

Finally, you ask about what the study of these writings has taught me about religion. This could be answered in a lot of different ways, but I think one very important thing to keep in mind is that there often has not been a hard and fast line between “canonical” and “apocryphal” – there’s slippage between the two categories. The best example of this is how “everyone knows” that Mary rode a donkey to Bethlehem, and Joseph walked along side of her. It’s in every single Christmas pageant! And yet, if you look at Luke’s Christmas story, there’s nothing said about how Mary and Joseph actually got to Bethlehem. The donkey only appears for the first time in a second-century apocryphal infancy gospel called the Proto-Gospel of James. From there, it found its way into later texts and artistic representations, and now it’s an official part of the Christmas story – despite being found nowhere in the Bible!

Thanks so much Brent for sharing your thoughts and knowledge with us. It is an fascinating topic to continue researching for more discoveries. You have given us much to contemplate. Have a Merry Christmas!

.

.

Fantastic interview, Jenny.

On the topic of the idea that the Son of God might have been behind all early religions and “deities”, it reminds me that years ago I saw a documentary that claimed that the early native American Indians were visited by a wandering prophet that very much resembled Jesus in nature. And that that played an important role in how those peoples initially accepted the Spanish when they arrived.

I have no idea about the accuracy of that, just something I recall seeing.

Are you aware of anything like that?

Thanks……I’m not sure if you might be thinking of the story about the serpent god- Quetzalcoatl and the belief of the natives thinking Cortes was this god- returning to them- when he first visited. Which some feel attributed to their demise. ???

I don’t think so. But I can’t say that what I saw was complete, either. It sounded more like a wandering man who had a “word” of peace and love to spread.

hmm…. a mystery to solve! I will have to look more into it…lol….

A great article, Jenny and Brent.

I like how the Revelation of the Magi attributes the Star appearing in the sky to Christ Himself.

That really rings true with my beliefs…that all Good Things point to Christ.

Colossians 1:17 And he is before all things, and by him all things consist.

John 8:12 Then spake Jesus again unto them, saying, I am the light of the world: he that followeth me shall not walk in darkness, but shall have the light of life.

Thanks JC1117…… the whole manuscript is so interesting. And yes, like you say, it just relates and offers more.

It also sounds like the Grail. It too was supposed to change shape.

I always thought of that as more like the Holy Spirit. One and the same but in different aspects.